So much press lauding these decisions. They should read them with a different eye, Dark Horse especially.

“Dark Horse,” “Stairway,” and “Blurred Lines” collectively had composers paralyzed with fear, right? Plenty of other big songs found their way to litigation in the past few years, but “Dark Horse,” “Stairway,” and “Blurred Lines” get all the attention. Is it because they contributed so much to case law? Nah. It’s because they all went haywire in court, one way or another.

All three prompted condemnation from musicians, composers, and vloggers, and were the inspirations for amicus briefs and magazine articles about a “climate of fear,” a Bizarro Universe brought about by three goofy trials in which creatives couldn’t create without fear of frivolous litigation coming at them. We want creators to create, so a climate of fear is a damned shame.

In the past couple of weeks, however, Stairway was upheld, it doesn’t infringe upon Taurus; and also Dark Horse was overturned; it no longer infringes on Joyful Noise. Hurray! Everything’s right side up again, so should the climate of fear subside? It really depends on your point of view I guess.

Skidmore’s (Taurus) attorney, Francis Malofiy told NPR last week on the day of the decision, “Zeppelin wins on a technicality. And I think that’s very disheartening for the creatives, and it’s a big win for the multibillion-dollar music industry.” (This was in that same piece I was interviewed for. I should post the link in here somewhere (link).) Anyway, he’s clearly saying “this was good for the bad guys,” But for the most part, the stories being written are about terrible unjust verdicts getting reversed or avoided, and how creatives should feel somewhat more solid ground beneath their feet.

So let me throw cold water at that, beginning with Stairway.

There was some good news; they have finally killed off the silly inverse ratio rule. That’s nice. But forever the big thing will be this: nobody compared the acoustic guitar intro to Stairway to the acoustic guitar intro of Taurus, though that’s what the case was about for all intents and purposes.

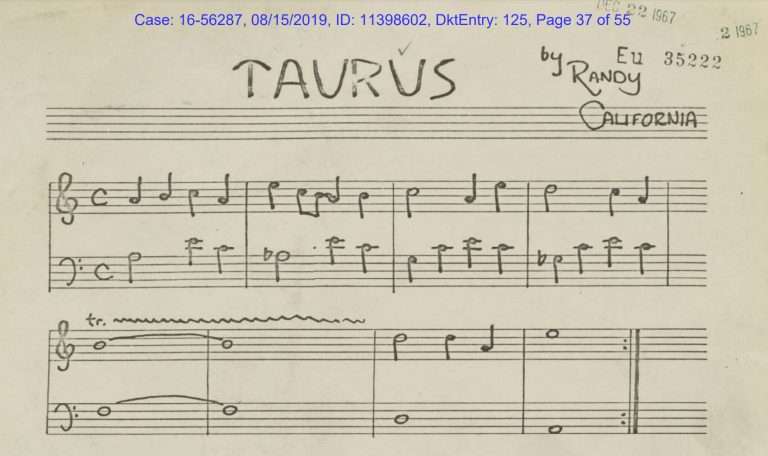

(In case you’ve been under a rock) That music was never heard in court, and instead the ONLY thing the plaintiffs were left defending copyright of was this, the registered deposit copy:

And the sheet music sounds, roughly, because it’s an iffy transcription, like what you’ll hear if we start Taurus at a middle section of Taurus which features strings more than acoustic guitar. Here’s Taurus from that point:

There are a dozen youtube videos out there comparing Taurus to Stairway. None of them play that! Because who cares?! They ALL play the part of Taurus that sounds like Stairway.

Legally, it all made sense. When Zeppelin’s attorney got the Taurus recording disqualified, the case was substantially won. And that’s not to say he wouldn’t have won anyway; in fact I think he would or at least should have. But juries are unpredictable as I’ve said that here repeatedly.

Does this do anything at all to mitigate the climate of fear? Did we get anything on what’s original vs. what’s commonplace? Nope, “climate of fear,” unaffected.

“But wait, that Dark Horse thing was some bullshit, right?”

Right. But…

I’ve said a zillion times, it was a bad verdict. But I also admit this decision took me by surprise. At any rate, its reversal helps set things right, doesn’t it?

Eh, yes and no. Mostly no. The rationale puts things on iffy footing for me. In fact, I won’t be surprised if this flips back.

Again, yes, it arrives at a good result, that Dark Horse doesn’t infringe upon Joyful Noise because the similarities that might exist between them are not protectable by copyright. Questions of access and copying aside, it’s not infringement. (The terms get used interchangeably, but really “copying” is distinct from “infringing.”) And with the inverse-ratio rule perhaps truly gone, even if Katy Perry DID hear Joyful Noise prior to writing Dark Horse, it’s still not infringement. None of which I’ve a problem with; to the contrary.

Also, the decision is laid out super methodically, densely packed with references to case law, and just impressive as hell in a lot of ways, in part perhaps because I am not a lawyer.

The underlying reasoning though?

It begins that the extrinsic test (the musicologist stuff) needs to (1) identify the protected elements of the plaintiff’s work and then (2) determine if they’re similar to the elements in the infringing work. (way more practical to do these in the reverse order, btw.) Next, it gets into “selection and arrangement” — a concept where a bunch of unprotectable stuff might theoretically become protectable only “as a unique arrangement” of that unprotectable stuff. (Makes sense for phonebooks, computer designs, and in some circumstances, music.)

This turns out to be the whole framework — to first consider the protectability of the elements on their own, and then when that fails, which it will, the protectability of the selection and arrangement of those unprotectable elements.

We’re going to consider the protectability of “elements” of music, so it would be nice to know what that means.

google: "elements of music"Google says among other things…

Google is evidently willing to provide a different answer depending on how many elements I’d like there to be in music. And this exemplifies my first concern. Is “melody” the first element? It might be. And what’s melody?

Wikipedia says: A melody (from Greek μελῳδία, melōidía, “singing, chanting”),[1] also tune, voice, or line, is a linear succession of musical tones that the listener perceives as a single entity.

If however “melody” is your first element, where do you put “pitch?” Is “pitch” not an element of “melody?” And if you next suggest, “rhythm,” I might say, “Isn’t rhythm an element of melody?” And “rhythm” has the elements of “duration” and “time placement.” Are those “elements?” In other words, what’s the hierarchy here? What’s an element of music versus an element of an element?” I don’t think it’s a pointless consideration. It will have logical ramifications.

In consideration of “individually protectable elements” the decision describes the Joyful Noise musicologist’s assertion of several protectable elements in its ostinato — phrase length, rhythm, pitch, timbre, and use or placement of the ostinato within the songs — and notes that his testimony doesn’t claim these are each individually protectable, but that they’re similar to both works and not found in prior art. The decision next quotes him as “conceding” that any single element would not have been sufficient, although the combination of them in his view was.

Then the decision takes from that concession the implication “that if the ostinatos are similar at all, it is reasonable only as a result of the arrangement of elements within those ostinatos, not any similarities between the individual elements themselves” and “Plaintiffs’ burden to present evidence that establishes the protectability of each individual element is not met when their own expert provides testimony that assumes the opposite.”

But a melody is not a “selection and arrangement” of pitches, rhythms, timbres, etc. Not per se. It involves a combination of these qualities, yes, but not a “selection and arrangement” just as a Van Gogh painting of purple irises is not reducible to an arrangement of reds and blues. The purple irises are an original idea even if you have no claim to reds, blues, and flowers. That’s not selection and arrangement, for if it were, then what would not be?

But the court reasons that if the plaintiff fails to either establish the protectability of the ostinato’s elements on an individual basis, or failing that, selection and arrangement, it hasn’t met its burden. And thusly it proceeds down the following list — really letting the appellant steer in my view. And I’ll look at each point, the plaintiff’s “concessions” (paraphrased for brevity) in italics and my reaction following.

On the protectability of the individual elements, the decision says the plaintiff’s musicologist conceded the following:

So all of these are like asking him to concede that water is wet. And sure, there have been numerous litigations where the complaint is, “Our melody begins with a long note and so does theirs!” whereupon you ask, “don’t a lot of melodies begin with long notes?” But this is not that.

I take it all of the former was from the original trial. Then we do the same sort of thing with this, I guess revised list of elements of similarity — evidently from the opposition to the appeal — which I’ll treat similarly, the “element” in bold follwed by the court’s response in italics, and then my comments.

(1) Melody built in the minor mode. Court responded, “First, the key or scale in which a melody is composed is not protectable as a matter of law.” Joyful Noise and Dark Horse are in different keys, so this refers to the minor scale tones that comprise the respective ostinatos, which can serve to imply some functional similarity between the non-identical pitches. It is not an argument that keys or scales themselves are protectable.

(2) Phrase length of eight notes. “Second, plaintiffs concede that a phrase length of eight notes is not an independently protectable musical element.” I’m gonna keep saying basically the same thing… If the argument were, “my melody is 8 notes and so is yours, and so while your notes are all different pitches and placements from mine, I just think it’s interesting that they’re both 8 notes long,” you’d say, “go away.” This is not that.

(3) Pitch sequence begins identically ‘3,3,3,3,2,2.’ “Third, a pitch sequence, like a chord progression, is not entitled to copyright protection.” In what physical universe? We’re just conducting an exercise about an artificial situation wherein a pitch sequence could somehow be expressed entirely without rhythm or timbre such that it could be in any way productive to consider if the sequence alone would be protectable regardless of rhythm.

(4) A similar resolution to both phrases. “Fourth, because the way that the ‘Joyful Noise’s’ ostinato resolves is determined by rules of consonance common in popular music, it is not the type of musical element that is protectable as a matter of law.” All resolutions determined by the rules of consonance, it’s the nature of resolution in music.

(5) A rhythm of eighth notes. “Fifth, plaintiffs concede that a rhythm of eighth notes is commonplace.” Not “eight” this time, but “eighth.” We can do this all day I guess. If I describe two melodies as having the same rhythm, that’s a similarity. If it’s straight eighths, that’s a commonplace similarity but a non-zero one.

Sure, it’s perfectly true that a bunch of commonplace similarities do not necessarily add up to significant similarity. That’s why Blurred Lines was bullshit. But a bunch of commonplace similarities don’t make for a necessarily unprotectable melody. This is the fallacy.

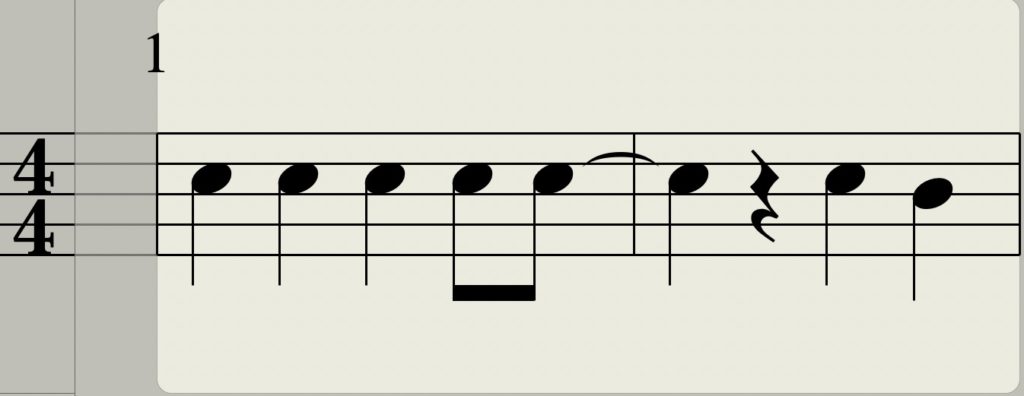

Consider the following example:

And what have we there?

Not protectable?

How about this one?

That’s 30+ consecutive notes of identical duration and from one major scale. Maybe the greatest melody that ever was. Broken down as we have the ostinato in Dark Horse, it would check most of the same boxes.

In other words, we’re discussing whether the elements (“properties” or “aspects” or “qualities?”) are in and of themselves protectable? But how few popular music elements would be? This is better suited to illustrate an absurdity, such as, “Song A is about a spaceship, and so is Song B. I published A first, so B infringes.” That’s what we mean when we speak of “ideas” that are not protected by copyright as opposed to expressions of ideas which might be.

Imagine if the trier of fact asked, “So, Musicologist, you’re showing an “A” followed by a “C” followed by a “G,” repeated again, then an “A,” and “C” again followed this time by a “B?” (“Come with me and you’ll be in a world” (of pure imagination.) Well, Musicologist, can one copyright an “A” or a “C” or any of those other elements?”

At this point, before getting into the considerable “arrangement of unprotectable elements” portion of the decision, everything to this point seems to me to be a pedantic and pointless exercise. And logically makes no more universal sense than did the inverse ratio rule.

And it’s a big damned deal! This has got to move the odds on the Sheeran v Townsend case? And what prevents Blurred Lines from being overturned by the same logic? The Yellowcard v JuiceWRLD case is still looming and I’d say that landscape just shifted considerably.

I have opinions on all of these! Dark Horse — its ostinato, in particular — is NOT similar in a musicologically significant way to that of Joyful Noise. It was a wrong verdict. But however strongly held, this is my opinion. Ruling it as a matter of law for the reasons I’ve absorbed so far? I find no comfort in that.