Whatever the record is around here for the quickest complete dismissal of an infringement claim, I expect to challenge it today.

The accused work, “Dare To Know,” by Yes, whom I’ll disclose I listened to constantly in my youth, does not infringe on a cue from the movie “A Winter Rose,” which I don’t plan to ever see because watching Paul Sorvino weeping in this clip, along with the plaintiff’s perfectly pretty and sad melody, was heart-wrenching. He was a tremendous actor.

Here are both songs. You’ll only need to listen to the first little bit of the Yes track to know what we’re talking about here.

Certainly, we do hear it. This is about a bunch of four-note descending figures that aren’t alike, but a plaintiff believes and perhaps has been told otherwise.

Behind both of these melodies is a basic compositional device, a widget type of a thing that has a name, a “sequence.” Sequences are a basic tool in a composer’s toolbox, a sort of mechanized melody, like a math function with a set of rules such as “start on a number, add three, divide by 2, add three, divide by 2…” And off you go. 1, 4, 2, 5, 2.5, 5.5, 2.75.

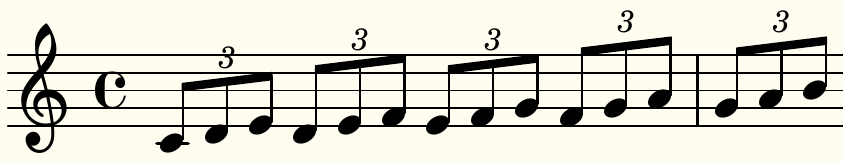

Let’s do it with notes. Here’s a simple and obvious musical example (not from this case, but just to help illustrate) Imagine groups of three: “Do-re-mi, re-mi-fa, mi-re-sol, fa-sol-la, … and so forth. Can you see it? We might express it more numerically: our everyday do-re-mi major scale contains eight notes, we’ll number them 1 thru 8, and this sequenced melody is 123 234 345 456. And lastly, written on a musical staff, it would look like this…

If two composers write that into their works and one sues the other, a poor analysis might focus on the unlikeliness of “so many identical notes in a row, and with the same durations per note!” or similar, as though each note were its own compositional election, but it would be nonsense. Any five-year-old who stumbled to my piano might accidentally discover and play this figure all the way up the keyboard until he runs out of white keys. The melody, in a sense, wrote itself.

“YES” can’t monopolize that aspect of their melody any more than this plaintiff can his. Mechanisms like these are the stuff of elementary musical exercises.

So if YES’s sequence was quite a bit like the plaintiff’s, the plaintiff’s may well not be very protectable. Strike one.

But, well, it’s not quite a bit like the plaintiff’s! The unprotectable mechanisms in these two works, or to put it in math terms again, their “functions,” are not even very similar. That’s strike two and three, but I’ve got another few minutes before my next call, so…

It would be sorta true to say that the respective series of four-note melodic cells share fairly similar (though not identical) rhythmic placement, depending upon what time signature I apply to the movie clip, and good old “melodic contour” (yeah, they go downward) but none of would be at all compelling because (again) the pitches are quite different — at a glance, about 75% different. And that’s way weird because although I haven’t read the complaint, a few articles have reported that an expert claimed these melodies were 96% the same in terms of pitch! That’s indefensibly untrue. I’m at a loss. If they were 96% the same, they’d only be 4% different. But they’re about 75% different, so that’s nineteen times more different than this expert did. I’ve never come remotely close to such a disparity. We could quibble over my 75% number, but I can’t think of any defense of the plaintiff’s analysis.

And we ain’t done! Besides the notes, the accompanying harmonies that give the notes context are different. And basic modes of the two compositions (that’s major and minor type stuff) are, you guessed it, different.

Geeze. Stop the clock. It’s just not that interesting. This case shouldn’t have been brought, and the mere fact that the plaintiff has an analysis in hand shouldn’t burden YES with needing to swat it away. This is not, “Happens all the time; two experts just disagree.” That would be ridiculous here. One of us is saying the earth is flat. Summary judgment should simply say otherwise.